This article outlines the current statutory framework for availing Safe Harbour protection under the IT Act and the areas of challenge in the existing law.

It is a selected excerpt from our series tracking the Evolution of Safe Harbour provisions in India, available here.

A further excerpt summarising our observations on the impact proposed amendments to intermediary guidelines are likely to have is available here.

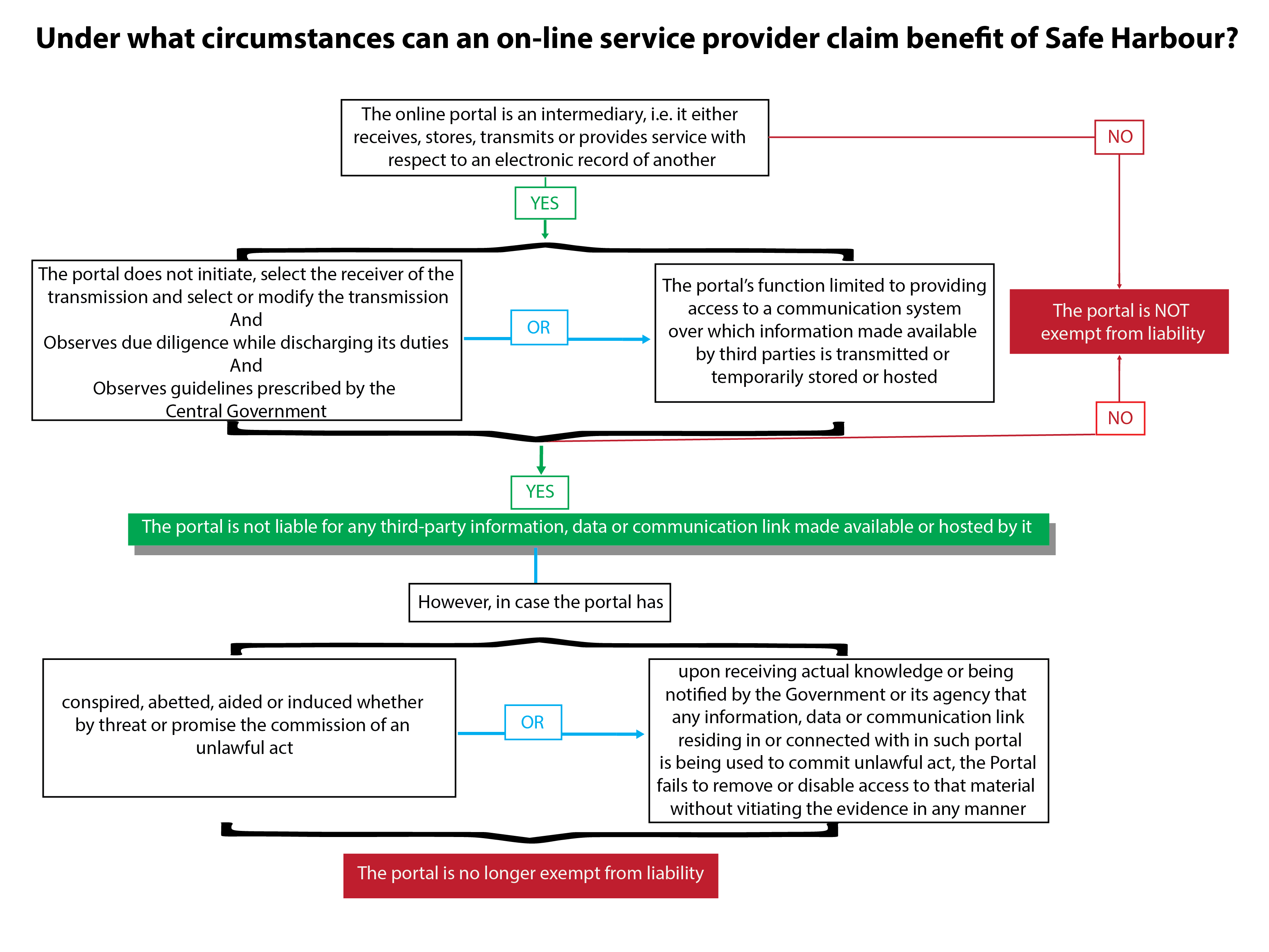

In the on-line world, Safe Harbour provisions protect the people and enterprises who provide the underlying infrastructure, also known as intermediaries, from liability for the acts of third parties who use this infrastructure for their own purposes. For e.g. Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are not liable if their subscribers use the internet for unlawful acts, Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) are not liable because people store illegal data on their server, e-commerce platforms are not liable if people sell spurious goods and social media platforms are not liable if people post defamatory content.

Safe Harbour provisions are found under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”)[1]. Section 79 (2) lists out the requirements to avail safe-harbour protection. One of these requirements is the observance of guidelines prescribed by the central government from time to time. The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2011 (“Intermediary Guidelines”)[2] are the primary guidelines which intermediaries need to observe to avail safe-harbour protection. These guidelines list out the due diligence requirements that must be observed by intermediaries to avail the safe-harbour protection.

The current framework for safe-harbour protection in India is illustrated in the flow-chart below.

Areas of Concerns

- The conditions for seeking Safe Harbour protections are too stringent and have lost sight of ground realities. Particularly, the stipulation that that intermediaries should not “initiate, select the receiver of the transmission and select or modify the transmission”, is unduly harsh. The purpose and function of an intermediary is to facilitate transaction and/or transmission of data initiated by their users. This would in many instances, necessarily involve structuring the environment in which such transactions and/or transmissions take place. This is especially crucial for e-commerce intermediaries operating in new markets wherein the sellers may lack the technical skills/knowledge to optimise the display of the information relating to their products. Even in developed markets certain activities undertaken by intermediaries such as indexing of content, targeted advertising based on user preferences etc., enrich user experience and are considered indispensable.

For more on this please refer to our discussion around passivity and the observations made by Delhi High Court’s in Christian Louboutin SAS vs Nakul Bajaj and Ors. (2014 SCC OnLine Del 4932) in Part II of this Series.

- It is unclear when an intermediary can be deemed to have “actual knowledge” of an unlawful act on their platform. For a while it seemed that the standard for actual knowledge had been set by the Supreme Court in the Shreya Singhal v Union of India[3] case which broadly held that ‘actual knowledge’ would only be through a court order. However, in the matter of Myspace Inc. v. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd[4], the Delhi High Court held that the Shreya Singhal standard was only applicable to social media intermediaries. Consequently, the ambiguity on when an intermediary can be deemed to have actual knowledge remains.

For more on this please refer to our discussion around the interpretation of the terms “actual knowledge” in Part II of this Series.

- Recently in the matter of Swami Ramdev and Anr. vs. Facebook Inc. & Ors[5], the Delhi High Court has opined that take-down requirement imposed on intermediaries mandate a global take down of any unlawful content uploaded from India. It is pertinent to note here, that most intermediaries operate on a global scale and what may be deemed to be unlawful in one jurisdiction may not necessarily be deemed to unlawful in another. Thus, intermediaries will be being forced to take down content which is deemed to be unlawful in India across the globe. This may make them liable for action in some other jurisdiction where such content is legal for an unlawful takedown.

For more on this please refer to our discussion around Global Takedowns in Part II of this Series.

Authored by Tanya Sadana, Senior Associate Ikigai Law with inputs from Anirudh Rastogi and Aman Taneja

References –

[1] The Information Technology Act, 2000 was enacted by the then Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs vide Extraordinary Gazette publication dated 9 June 2019. The IT Act is available at https://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1999?view_type=browse&sam_handle=123456789/1362 (Last accessed on 2 April 2019).

[2] The Intermediary Guidelines were released by the Department of Information Technology, Ministry of Communication Technology vide G.S.R. 314(E) dated 11 April 2011, in exercise of the powers conferred by clause (zg) of sub-section (2) of Section 87 read with sub-section (2) of section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. The Intermediary Guidelines are available at https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/in/in099en.pdf (Last accessed on 02 April 2019).

[3] Shreya Singhal v Union of India, (2015) 5 SCC 1

[4] Myspace Inc. v. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd, (2017) 236 DLT 478 (DB)

[5] Swami Ramdev and Anr. vs. Facebook Inc. & Ors, CS (OS) 27 of 2019, available at http://lobis.nic.in/ddir/dhc/PMS/judgement/23-10-2019/PMS23102019S272019.pdf